Suffering the effects of a major illness can feel scary and isolating. Getting through it takes not only medical assistance but emotional support. In the story that follows, my friend David Fisk tells of four “asks” that loved ones made on his behalf during a health crisis he faced ten years ago. Part of David’s story involves asking in prayer, a topic outside the scope of my book and blog but integral to his experience. Here’s David’s story in his own words.

___

My grandmother, whose name, appropriately, was Grace, had a great deal of influence on me. I spent a lot of time at her farm. When I was young, she would take me for walks. We’d cross the road to an old wooden gate and follow a forested trail along a creek, listening to the water. She’d talk with me about a lot of things.

During one of these walks, she said, “So, you’ve got a birthday coming up.”

“Oh yeah!” I said. “I really want a two-wheel bicycle. I hope I get one!”

“Well, you should pray to God if that’s what you really want,” she replied. “God will always answer your prayers.”

This was about two or three weeks before my birthday, so I got on that! I prayed and I prayed.

My birthday came and went. I didn’t get the bicycle.

My family wasn’t in great financial shape, so I wasn’t completely surprised. But I was disappointed. The next time we went on a walk, I said, “Grandma, I prayed and prayed for that bicycle and didn’t get it. You said God always answers prayers.”

And she said, “God did answer your prayer. He said no.”

She tried to make me feel better about it: “Maybe if you’d have gotten that bike you’d have been hit by a car. Maybe there was an accident that was going to happen that won’t happen now. Whatever the reason, honey, God said no.” When it came to religion, Grandma would have an answer for anything. Her faith was unshakable.

About 10 years ago, I was teaching at a therapeutic day school when my doctor called with some shocking news. “You have advanced stage leukemia. You need to be in the hospital and on chemotherapy today.” I left the school and went right to the Kellogg Cancer Center, which became my home for the next month.

From the beginning, I started praying that I would make it, that the intensive rounds of chemo would work. But then it came back to me what my grandmother had said. I had all kinds of supportive people sending their prayers and supportive energy my way, but the possibility remained that the answer could be no.

Lying in that hospital bed gave me plenty of time to think about my situation and how I felt about my life. I wanted to live. But when I considered the possibility that I might not make it through, I started feeling really grateful for everything I had.

I was 62, had three great kids from a wonderful marriage that had lasted 25 years, warm and solid friendships, a wonderful relationship with my partner, Nancy, and no unfinished business or big regrets. I had always been in some kind of rewarding work, loved going to college and training to be a teacher and now working with kids with emotional and behavioral problems.

And there was a lot more I wanted to do. If the answer to my prayer, “Can I please be healed?” was no, I felt in some way that I could go on a peaceful note.

One morning shortly after I came to this realization, my eyes opened to the first rays of the sun pouring through my hospital window. At that moment I could see, all over the window and hovering in front of and beyond it, dozens of bright red lip kisses, like those old Colorform stick-ons. And then they faded away.

I interpreted this as a symbol of the outpouring of love from people who were finding out I was sick — the cancer survivors at my church who were calling to check in on me; and the people of all different faiths who were praying for me and being supportive.

Were the lips a vivid dream or a chemo-induced stupor? Or something that broke through the stupor? Finally, I decided it didn’t matter. It had felt wonderful.

While I was asking for healing through prayer, Nancy, a professional artist and art instructor started asking her family to make and send me origami cranes to put up in my hospital room, instead of get-well cards, and gave them instructions on how to make them. She chose the crane for its traditional association with light, goodness, and longevity.

Next, she asked my school if she could teach my students to make the cranes. These emotionally disturbed kids who had routinely cussed me out and thrown things at me began creating origami cranes scrawled with their good wishes for my recovery.

And then my daughter Moira asked her Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority sisters at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne to get involved. These young women—only a few of whom I’d met— sent me a box filled with hundreds of cranes in pastel colors that had taken them a whole day to make. We had a hard time hanging them all! The hospital staff loved the garlands of cranes, saying how nice my room was to visit.

And if all that wasn’t already positive enough, Nancy’s sister Gail and sister-in-law Jackie told their yoga communities about me. They asked people to take photos of themselves in a yoga pose called the crane, a difficult pose that requires balance.

A few weeks later, in my hospital room, Gail opened her laptop and showed me the nearly 70 photos people had sent. It was such an eclectic group — slim, trim yoga professionals, a pregnant woman, a guy in prison, and one photo of a person who had gone to the top of a mountain to do the pose.

It was really overwhelming. I was extremely touched that all these people would come together in support of me, a guy most of them didn’t even know but felt for. It was wonderful knowing there were so many people in different places pulling for me.

At the conclusion of my seven months under his care, the oncologist told me I had responded to the treatments better than any other patient my age. The bone marrow transplant we had considered earlier would no longer be necessary. I have been in remission since then.

In her 80’s, when asked how she was doing my grandmother would say, “Kickin’, but not too high.” I never understood that until now but feel so incredibly grateful to be “kickin’” at all!

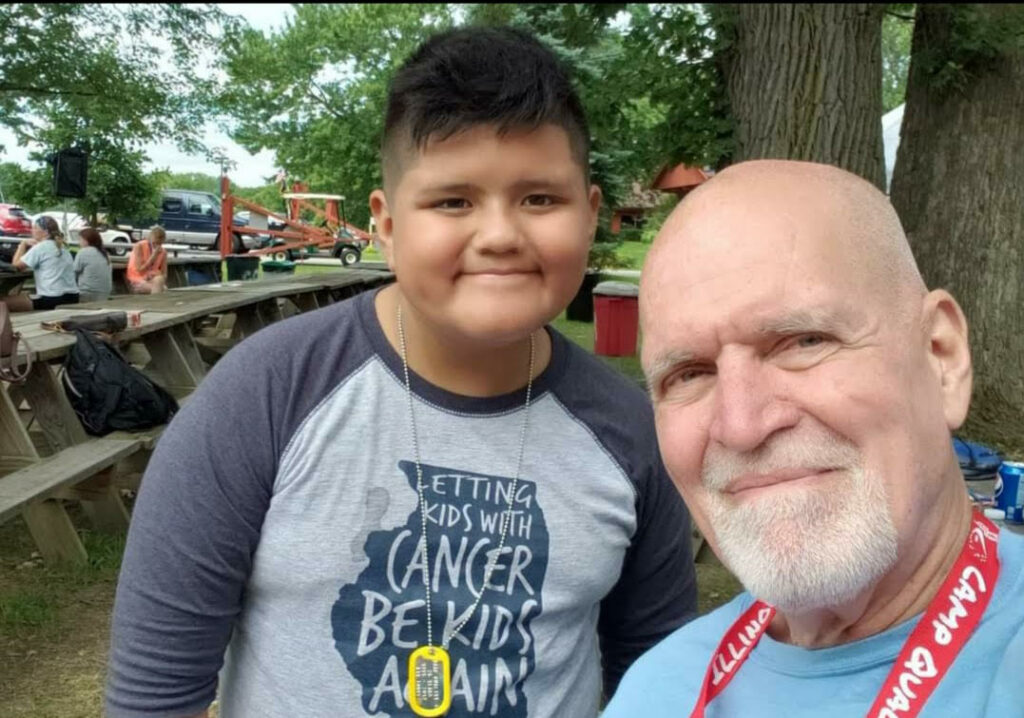

David Fisk retired from the Chicago Public Schools in 2012, where he had worked for 22 years as a Special Education Teacher in a therapeutic day school for children with emotional and behavior disorders. Previously, he worked 14 years as a social worker at Little Brothers of the Poor and Housing Opportunities and Maintenance for the Elderly. He has graduate degrees from Purdue, Arizona State and Northeastern Illinois in Special Education and Photography. David volunteers at Camp Quality, a residential camp for children with cancer (see photo above) and at the Chicago International Film Festival.

Paul Quinn is author of The Big Ask, a nearly completed book about asking as a life skill, which features portions of this content. He invites readers of this blog to contribute ideas, research, stories, or thoughts on asking.

0 Comments