A few years ago, after I gave a talk at Northeastern Illinois University on the subject of asking as a life skill, a student of Asian descent raised his hand and asked if I had any stories in my book from Asian people (at the time I didn’t). When I said no, he said, “That’s because Asians don’t ask!” which brought laughter from some of his Asian classmates.

There is no singular “Asian” culture, of course; variations between cultures are too numerous to specify. But asking for help, opportunities, and recognition may be particularly challenging for people from the collectivistic societies of China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, which traditionally value group loyalty over individual achievement. And that can present unique communication challenges for Asian people working in the U.S., according to Chicagoan Jim Lew, the son of Chinese immigrants.

In this interview, Jim talks about cultural differences in attitudes about asking, the human and corporate costs of not bridging those differences, and, on a lighter note, his regrets about what he failed to ask during his 16-year association with The Grateful Dead.

I met the remarkable Jim Lew many years ago when we co-led a training segment for Lucent Technologies. His career began as a teacher at Cooly High, in the public housing projects of Chicago. He later became a social worker for the State of Illinois and a psychotherapist before transferring his skills to the corporate sector.

Jim has trained and consulted with Hollywood producers, correctional institutions, police departments, city governments, as well as Fortune 500 corporations. As a trainer and presenter in the area of Diversity, his clients have included Hyatt Corp., Proctor & Gamble, Texas Instruments, Discover Card, T.J. Max, G.E. Capitol, and Harvard School of Public Health.

Paul Quinn: Jim, I understand you have a personal story to start our conversation.

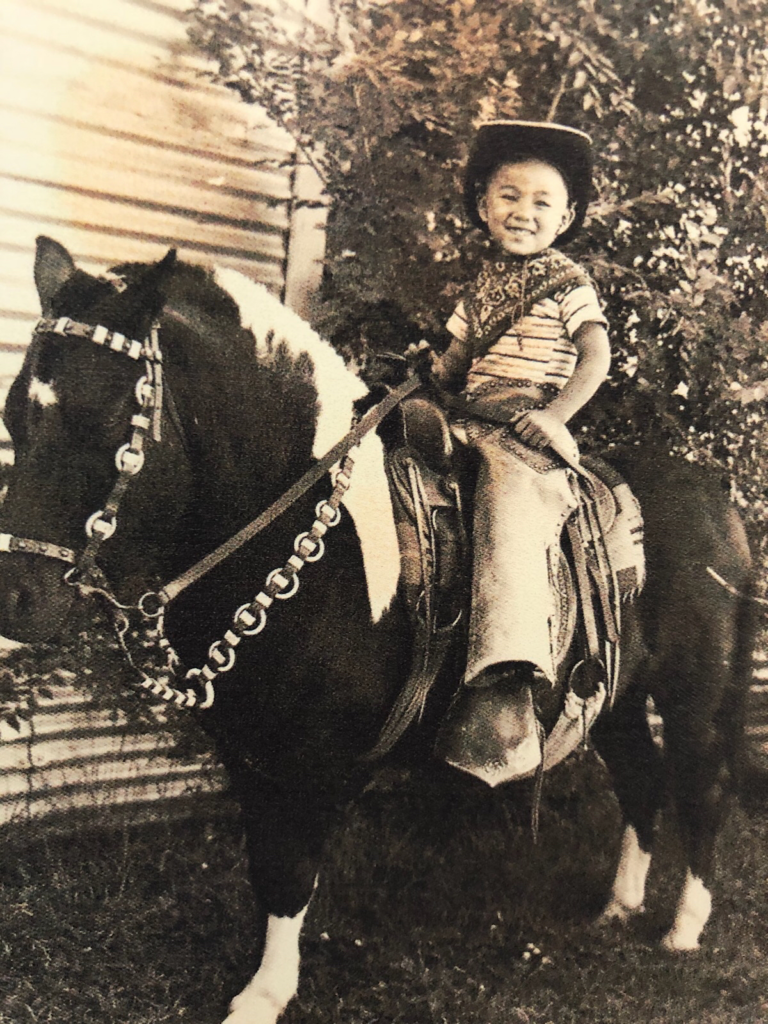

Jim Lew: Yes. My parents immigrated to the U.S. from the Pearl River Delta region in China. When I was a kid, we moved from Amarillo, Texas to Wichita. There was a Chinese lady who lived a few houses down and I remember sitting in her living room.

I saw a jar of candy on her coffee table and said, Can I have a piece of candy? Well, my mother was immediately “Oh my god!” and “How dare you!” You see, asking in the Chinese culture is not approved of. And the lady chuckled and said, “Of course you can have a piece of candy.”

Decades later, when I was in my 30s or 40s, we all took a trip to San Francisco. The neighbor lady had moved there so we thought we’d visit her. When we walked in, the first thing she said was …

“Oh, there’s the kid that asked for candy!”

So that’s the position of asking in the Chinese culture—the kid who asked for candy was remembered decades later!

It’s a real strong cultural thing: you wait until your time. That’s how you respect the culture. When you’re ready for things people will tell you. But don’t ask. And that includes your power as a person in the community.

You humbly work hard and you wait for somebody to offer you something or to give you a job or whatever, but you’re not expected to ask. You’re expected to wait and be noticed and work hard.

Paul Quinn: How does that reluctance to ask affect some of the Asian people working in U.S. corporations?

Jim Lew: Procter & Gamble was a client for 22 years. I was brought in to onboard all the Asian scientists and researchers from China, Vietnam, Korea, Japan. My job was to tell them how to succeed in America because Procter & Gamble had a high rate of losing Asian researchers just a year or two into their careers.

You know, in a year of two you’re just barely learning the corporate culture. And they calculated that when somebody quits in the first two or three years the company loses about a quarter-million-dollar investment in that person, all the time and training, and then rehiring and retraining somebody else.

So, I’d come in and do these multi-day workshops with the new Asian recruits, and part of it was about asking. Asians are really bad on exit interviews because they don’t want to say unpleasant things or burn bridges.

But in reality, they’d leave over things that were painful to them like working on a project, working very hard in the lab, and when the product and patent came out their name wasn’t on it. And even though Asian people don’t ask, they noticed and were very hurt about not being acknowledged.

And in a white culture the manager would say, “Well, if you wanted to be recognized you should’ve said something about it.” But for an Asian to say, “I think my name deserves to be on that patent” is something they choke on. It’s just not what you do.

And the consequences were serious for Procter & Gamble. The company hires only from the top five percent of any class and were hiring very expensive people and losing them. But the company was expecting them to be very American, like, if you want something, dammit, ask for it! If you want a raise ask for it! Name on a patent? Ask for it!

And yet, even after being told to ask we Asians are trained to be very reluctant to do so. In the Chinese culture, you’ve heard the phrase, The nail that sticks up is the one that gets hammered back down. And that’s a very common phrase. You don’t want to stick out. You don ‘t want to hold up your hand and say, “I want that.”

Paul Quinn: Is this something you struggled with in places you’ve worked?

Jim Lew: I remember from my education and often in my work somebody saying, “Well, who wants to take the lead on this?” And some white person would raise their hand and say, “I want it.” And I would be qualified and want it too, but I just didn’t feel it was right for me to stick up my hand and grab for it.

So, somebody else would get it. And I’d get that tight feeling in my throat. Because it was really something that I wanted.

I understood the Asians at Procter & Gamble. I felt just like them. I’m born in America but was raised by a very Chinese mother and father. My mother was kind of the driver in the family, but it was wait your turn.

Paul Quinn: Growing up, what did you ask for in your family?

Jim Lew: My brother and I were American enough that we would ask for things. My mother had her standards. You could ask for things that were involved in education and were likely to get them. I could get a microscope, a telescope. I had a little lab in our basement. But if I was to ask for a record album, my mother would be, like, “Are you kidding?”

Unless I could prove there was a lesson in the record album, my mother wouldn’t approve of the purchase. So, everything was filtered through the value system of my parents, and mostly my mother who was the driver.

Paul Quinn: In some cultures, there are different “ask” rules for males and females. Do those distinctions exist in China?

Jim Lew: I know there are gender differences in the Chinese culture that affect women differently, but my experience is that all children, male and female, are expected not to ask. The experience of keeping your head down and not asking and not appearing egotistical that you should elevate yourself above your peers.

I think we see a lot of that behavior forced upon the Chinese during the pandemic. You’re expected to conform and if you don’t, they’re going to weld you into your apartment building for several weeks. And you’re not supposed to ask for another situation, you’re supposed to accept it along with billions of other Chinese.

Paul Quinn: Getting back to Procter & Gamble for a moment, what advice did you have then, and do you have now, for companies looking to communicate more effectively with their Asian employees?

Jim Lew: I believe you have to create small group opportunities, small processes, where managers encourage people to speak up and ask. In facilitation training we learn to ask questions that can’t be answered with just yes or no because they’re conversational killers.

Instead, it’s “What are your ideas here?” or “What would you all like to do?” Encourage them to come up with content rather than asking, “Do you like it or not?”

Paul Quinn: Which is good leadership regardless of the employee’s culture [see my interview with G. Dan Lumpkin on the necessity for organizations to move from a “tell culture” to an “ask culture.”]. Let’s talk about your family. There is always potential for cultural conflicts between first-generation kids and their immigrant parents. How was it for you?

Jim Lew: I’m the Chinese kid that was raised on Route 66 in Amarillo Texas, so inside the home my mother forced me to learn Chinese first. She was well educated in China, a teacher, and spoke a lot about Confucius and other Chinese philosophers.

She would lecture me in high philosophy, and I’d shake my head and say, “Mom, I have no idea what you’re saying!”

My best language was English and hers was Chinese and in some ways that was kind of sad because we never communicated at a high level. We were more reactive, like, “Why are you doing that!” and “Get off my back!” type of thing rather than looking at the thinking behind what we were saying.

Paul Quinn: What were you like outside your family’s orbit?

Jim Lew: I became much more western in my external behavior and in organizations, where I was the president of almost every little club. I’m very un-Asian in that way. I was vice president of my high school and the student body president of my college [Grinnell College], and for those positions you have to run, which is asking.

That part of me is very un-Chinese and I’m kind of proud of it because I’ve seen the oppression that comes from training people not to ask, the lack of individuation, the lack of people knowing who they are. I think listening to my own questions is a way of teaching me who I am.

Paul Quinn: In my conversations with women and people of color I hear about biased questions, questions they are asked that wouldn’t be asked of people in the dominant culture. Have you been asked questions like that?

Jim Lew: Biased questions happen all the time. I was a theatre major. You would not know how many friends would say, “Would you come over and look at my Mac computer?” I’d say, “Why do you ask me that? I don’t know more about computers than the average consumer. Is it because I’m Asian?”

And they’d go, “Well …” and stumble around. But I am often asked by friends to take a look at their computers. And I say, “You really want a theatre major inside your computer? It may act up!” (laughs)

People look at me and think I must be technically competent because I’m Asian. That’s a common phenomenon in my life. Asians have some negative stereotypes, but I don’t take the brunt of it like my black or brown friends do.

Paul Quinn: As someone who’s curious about people, I’m intrigued when I meet someone with an accent I don’t recognize or whose name I can’t place on the map. But I stopped asking people “where are you from” when I began to realize that the question made some of them wary of me. They didn’t know if I was asking because I had a judgment about their country or nationality or something.

Jim Lew: Right. When you ask somebody where they come from it can be a negative thing because you’re saying obviously, you’re different than me. They wonder where I’m going with that when I ask those questions. And because I do diversity training, I’m so aware that intent and impact are so different. I need to make it clear where my intent is when I ask a question.

When I ask where they’re from I’m able to assure them I have friends from their part of the world, or I ask them to teach me a few phrases in their language. I’ve learned how to say hello and thank-you in many different languages.

Paul Quinn: Final question, Jim. Looking back, is there anything you regret not having asked?

Jim Lew: I met The Grateful Dead when I had a booth at the 1976 NAMM [National Association of Music Merchants] convention. Marty Lishon of the famed Frank’s Drum Shop called and asked me to get guest tickets for the band. I guided them around the convention, finding guitar booths for Jerry [Garcia].

I gave them some of my percussion instruments as gifts and [drummer] Mickey Hart put me on the backstage list. Their last night in Chicago that summer, Mickey asked if I would design some percussion for him, and that’s how our association began.

I was backstage with them every night they played Chicago, for sixteen years. I’d go back to the hotel with the band and out to dinner with them, and never did I ask to have my picture taken with any of them. I felt it would change my relationship with them from associate to tourist. Now that Jerry Garcia’s dead I think, GOD I wish I had a picture with Jerry!

To contact Jim Lew visit jimlew.com

Paul Quinn is author of a book-in-progress about asking as a life skill, which features portions of this content.

I love the questions you are asking and the answers. I would want a picture with both of you! Thanks