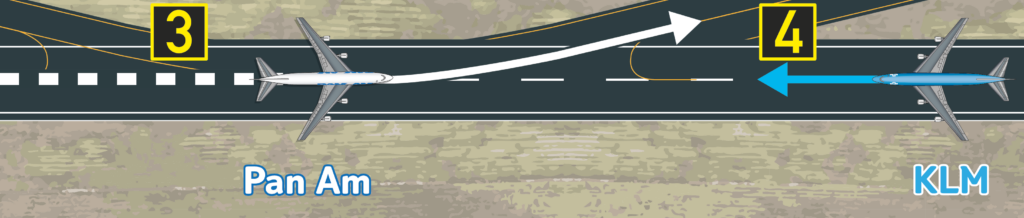

Shortly after 5:00 p.m. on March 27, 1977, at Tenerife’s Los Rodeos Airport in the Canary Islands, Dutch KLM flight 4805 sped across a densely foggy runway moments from lifting off when it rammed into Pan Am flight 1736 taxiing toward it.

All 248 KLM passengers and crew perished in the fiery collision. Only 71 of the 335 on board survived the Pan Am wreckage.

It remains the deadliest aviation disaster in history.

Extensive analyses of the tragedy over the years point to a perfect storm of conditions that made the unthinkable possible: extremely low visibility; radio interference; ambiguous communications between Airport Traffic Control (ATC) and pilots; confusion over runway positions; and the fatal decision of the KLM pilot to barrel down the runway.

Experts conjecture that the pilot made his decision because he believed he had takeoff clearance or that he could somehow safely bypass ATC protocols and hasten the plane’s much delayed departure.

But Jon Ziomek, author of Collision on Tenerife: The How and Why of the World’s Worst Aviation Disaster, believes there was an additional factor that contributed to the horrific events of that day: a deference to authority that made the KLM cockpit crew reluctant to forcefully voice their concerns about the pilot’s actions in the aircraft’s fateful final minutes.

“It’s the worst example I can think of in history of people being too intimidated by their boss to ask a question or challenge a decision,” Ziomek told me over Zoom. Flight recordings revealed that First Officer Klass Meurs initially protested when Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten advanced the throttle – “Wait a minute. We don’t have an ATC clearance.”

But Ziomek writes in his book that Meurs, who had the least flying experience of the three men in the cockpit, lacked the confidence to voice his likely suspicions that the Pan Am plane could still be on the runway.

“… how could Meurs question the man [the captain] who had certified him to fly in 747s only a few months earlier? Meurs had said only about 20 minutes previously, during the chatter among the crew members as they had sat near the terminal during the refueling, ‘The Basic Operating Manual states I have to obey captain’s orders first.’

What could Meurs do now? His newness, his uncertainty, his respect for the captain, his repeated use of ‘sir’ on the radio in the last few minutes – all, in retrospect, indicate a possible lack of self-assurance to speak out and question his commander.”

from Collision on Tenerife by Jon Ziomek

Second Officer and flight engineer Willem Schreuder was also confused by the radio communications he was hearing between Pan Am and ATC. In a desperate last-minute attempt to clarify the situation, he shouted to the captain, “Is he [the Pan Am plane] not clear then?” But Van Zanten couldn’t hear the question over the now-roaring engines.

Seconds later KLM 4805, charging across the foggy runway at over 100 miles per hour, smashed into Pan Am 1736.

“The entire system of aviation internationally changed after that flight,” said Ziomek, “when the airlines introduced the Crew Resource Management system (C.R.M).”

C.R.M supported a command hierarchy but pushed for open communication and collaboration in the cockpit. Co-pilots were now expected to express their opinions and question their captains if they saw mistakes being made. For their part, the captains were expected to admit fallibility, seek advice, delegate roles, and fully communicate their plans and thoughts.

“Had C.R.M. been in place back then,” Ziomek concludes, “I think the First Officer would’ve spoken up earlier with his concerns. He would’ve been more emphatic about saying, hey wait a minute — don’t start the throttle, you’re not following procedures here. Or he and the flight engineer would’ve felt more comfortable challenging the captain’s action rather than deferring to him.”

___

This post is dedicated to the survivors and over-500 souls who perished in the crash, 47 years ago today, on Tenerife. May it remind us to trust our concerns and perceptions and speak up with courage, especially in situations in which we might feel safer stifling our voices.

For a (related) story about how hospitals are standardizing processes to protect employees raising questions or concerns about patient safety, see my post Safe to Ask? A Chat with a Chief Nursing Officer.

“In one study investigating employee experiences with speaking up, 85% of respondents reported at least one occasion when they felt unable to raise a concern with their bosses, even though they believed the issue was important.”

– Amy C. Edmonson, author, The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth

0 Comments