What was it like to be the press agent for major Broadway shows and work closely with Yul Brynner, David Bowie, Lena Horne, and countless other stars? Joshua Ellis was the publicist for some of Broadway’s biggest hits, including more than a dozen Tony Award winners. He secured press coverage for the original Broadway productions of Into the Woods, The Elephant Man, 42nd Street, Fences, and the award-winning revivals of The King and I, Dracula, Peter Pan, and Morning’s at Seven (only a partial list).

Here, Joshua Ellis tells of his trial-by-fire with Yul Brynner, witnessing the professional stage debut of David Bowie, being in the room for journalist Ed Bradley’s famous 60 Minutes interview with Lena Horne, and an “ask” that captured a moment in history.

PQ: Josh, this might be an unusual way to start the conversation, but you mentioned to me that you have a story about a time you asked for forgiveness, an “ask” that changed everything for you.

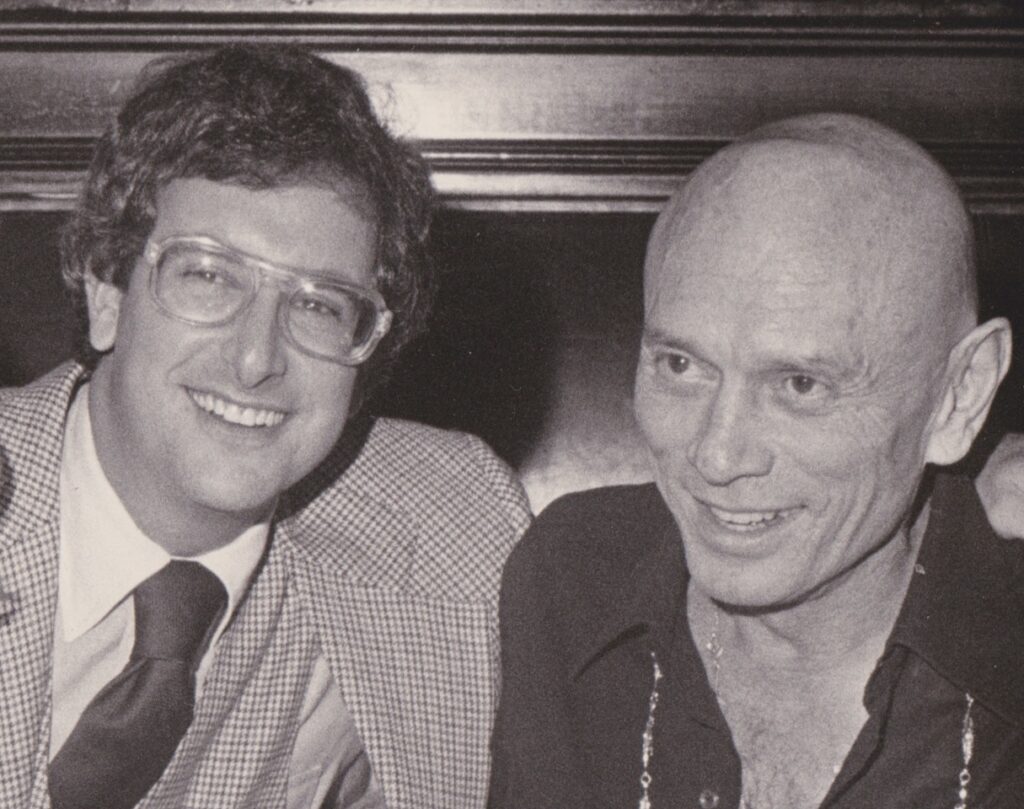

JE: In 1976, I worked for a big PR firm that was asked to do the press for a summer tour of The King and I starring Yul Brynner. It was the first time he had done the role since originating it in 1951 on Broadway and winning the Tony and then the Oscar.

Nobody in our office wanted to do it. The senior press agents had all been burned by Yul Brynner the year before on a new musical that closed after one performance, and Mr. Brynner had a way of chewing up and spitting out press agents. And because it was a summer tour with no particular cache attached to it, my bosses asked me to do it. And I was like, absolutely! Yes!

PQ: What made that such an easy “yes” for you?

JE: The King and I is my favorite musical. I had first seen the movie with my father at the Roxy Theatre in New York. I saw it dozens of times as well as many live productions of it and knew it backwards and forwards. So, to me it was a gift to do the show.

PQ: You worked on the summer tour. How did the show do?

JE: It was enormously successful. When its move to Broadway became inevitable, Yul Brynner asked if I would remain the press agent for the show. That did not please my senior colleagues in the office because the show was now a prestige item, and I was the young kid in the office.

PQ: What was it like to work on the Broadway run?

JE: The preparation was thrilling. Many of the talent who’d been involved in the original production came back to give it a helping hand including [composer] Richard Rodgers and [choreographer] Jerome Robbins and [costume designer] Irene Sharaff. Their contributions made something that was already very good superb, as only geniuses can.

Shortly before opening night, I set up an interview with Yul Brynner and the New York Post. He asked me who was interviewing him, and I said, “I never heard of her, she must be new.”

And with that simple sentence I unknowingly put my head into the noose.

On the day of the interview, I introduced him to the interviewer and left. When I came back an hour later, they were still chatting and everything seemed fine. But when I got back to the office, I got a call from the show’s producer. He said, “Yul Brynner is furious at you and demands that you come to his dressing room tonight at 7:00. It’s not looking good for you.”

And I had no idea why, which made it all the more upsetting.

PQ: Yes, I can only imagine. What happened next?

JE: At 7:00, there he is in his full King makeup—that fierce Oriental mask look—which works really great in a 2000-seat theatre but is scary up close.

And he says, “Do you know what you did today? The interviewer who you told me was new has been there for many years. In fact, she interviewed me in 1953 and wrote an article that said things about my relationship with my sister that caused a break in our relationship that never healed, and when my sister died, we were still not talking to one another. It was the same journalist, and you brought us together today.”

PQ: Devastating, Josh. How did you respond?

JE: What I said to him, I said not to keep my job, but because I felt I had betrayed a friend. I told him I had no excuse and that, though I knew I was going to be fired that that was irrelevant. I asked his forgiveness. I said, “I want to apologize to you because what I did was unprofessional. I should’ve checked out who she was. I apologize for hurting you.”

After an agonizingly long pause, he said, “Do you realize you’ve done something that no one involved in this production has done? You admitted you were wrong.” Then he quoted Benjamin Disraeli, who’d said that admitting you do not know something is the beginning of knowledge, but that it takes character to admit you don’t know.

And then he said, “Now we can be friends.” And he shook my hand and hugged me.

Admitting you don’t know. It was one of the great lessons he taught me. In the long run he became a father figure, mentor, and a friend to me. We stayed friends until the day he died.

PQ: When did he die?

JE: In 1985. The show closed because he was dying of cancer. His stays at Sloan Kettering [cancer center] were longer and longer. He and I collaborated on his obituary. He would dictate it and ask me to read it back to him.

At the end of The King and I, he’s dying on the bed asking Anna to take notes from the future king. And there I was, like Anna, literally taking notes. It was surreal. We finished his obituary three days before he died.

PQ: What a beautiful story.

JE: I am grateful for the privilege of having worked with so many people I grew to know and love. Because over the long run we shared each other’s humanity, including births and deaths and everything else. These were relationships, not like a movie press agent where you kind of get a can of film and you get the star for two weeks.

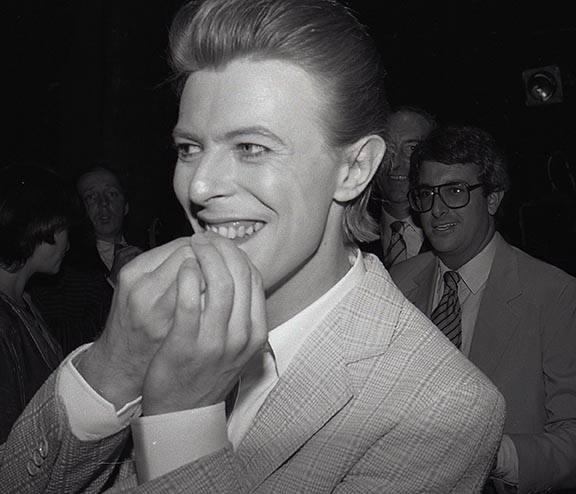

PQ: I want to ask you about another show you promoted, The Elephant Man. I’m a huge David Bowie fan and saw him perform the title role in 1981, at the Blackstone Theatre in Chicago.

JE: (emphatic) YOU. SAW. THE. BEST. I saw maybe 12 actors playing that role over the run of the show. There’s the other 12 and then there was David Bowie. He was that different. I adored him. I can’t tell you if I loved him more onstage or offstage. Everything about him was fantastic.

He approached the role like none of the actors who had done it before. And he was making me watch it again and again and again because he was so uniquely a creature of the stage. And there was his attention to people, his attention to the stagehands, to the environment of the theatre.

We did two cities out of town, Denver and Chicago, because he wasn’t sure he’d be any good in it and didn’t want to open cold in New York. He was a consummate professional.

The fun part of working with David was that he knew everyone. And they all came backstage after the show and his dressing room was the best party in town.

The people were so diverse. Mick Jagger would be there. Oona Chaplin was a frequent guest, and I could never stop thinking, You’re Eugene O’Neill’s daughter and Charlie Chaplin’s widow! I can’t even think of it now without it being too big a bite of a sandwich to eat! I didn’t invite the press to these backstage gatherings; it was just David’s friends and Coco Schwab.

PQ: Tell us about Coco.

JE: Coco Schwab was his everything, his secretary, his assistant, his best friend. She was always present with him. He said she saved his life, and I don’t question that for a second. To know him was to know her was to know them. And I adored them both; they were beyond wonderful. It was a great experience.

PQ: Any particularly memorable moments working with Bowie?

JE: Toward the end of his Broadway run in the Elephant Man, he asked me to be his personal press agent. And I didn’t think it was a good match because I didn’t know the world of rock music. I only understood the theater aspect of his universe. I knew that to get involved with him would be an investment learning about these other universes he lived in – his music and film careers. It felt overwhelming.

But we had a lovely talk and understanding about that, and it made us bond more. I would’ve loved working with him.

PQ: It’s hard to believe he’s been gone for eight years now.

JE: I felt so badly when he died, largely because I felt he could have done so much more in the theatre. He would’ve been an amazing Hamlet. He’s the only actor I can think of that could do Hamlet and Peter Pan and bring something unique to both of those infinitely complex roles.

PQ: He would’ve been a terrific Captain Hook, too!

JE: He could do anything. It was like meeting a Renaissance man and truly not knowing how to deal with all those facets. I had Barry Manilow as a personal client, but his universe was a whole lot easier to deal with. Manilow lived in New York at the time, it was early in his career, and there were no peaks and valleys at that point – only peaks. It was all ascent. And, for a press agent, ascent is really, really easy to deal with.

PQ: You were also Lena Horne’s press agent for her 1981 show, The Lady and Her Music. I recently watched the powerful interview Ed Bradley did with her then for 60 Minutes.

JE: The greatest interview I’ve ever watched happen. As part of my job, I was in the room. We were in a guest room in the Wyndham Hotel, where she lived. In the interview, the two of them got to a level of personal revelation about childhood and race and sexuality—questions that only he could get away with asking—and she’s batting them right back to him, and it was like watching two people have sex. It was that intimate. And they both cried copiously.

But when the interview aired, his crying was edited out, so it looks like she’s just crying telling her story. But, in fact, they were sharing tears. Ed Bradley said it was the greatest interview he ever did. And it was the one that 60 Minutes ran after he died.

PQ: And it was during the run of that show that you made perhaps one of the biggest asks of your career, Josh. Tell us about that.

JE: In 1981, before a performance of Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, Jacquelyn Kennedy Onassis walks into the theatre with Mike Nichols. As the press agent for the show, I see this photo op and I’m salivating.

Mrs. Onassis was as close to royalty as America ever had, so naturally I want to get a photo with her and Lena Horne after the show. But it was a big ask because of who she is and knowing I’m about to ask her to do what she famously doesn’t like to do at all – pose for pictures. She was really press-averse.

So, I approach her, introduce myself, and say, “Could we possibly have a photo op with you and Miss Horne after the show? It’ll take just five minutes.”

At first, she charmingly deflects my request saying, “Oh, who would care about a picture with me and Lena Horne?” But I smile and give her a look that says, We both know perfectly well you don’t mean that. And rather than ask her again, I simply say, “I’ll meet you at your seat at the end of the performance and escort you backstage.” And she agrees to the photo, though I’m certain it was not my power of persuasion that changed her mind but her respect for Lena Horne.

And then the evening gets even richer.

In the lobby I see Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr. And I know I have to get a photograph with them together.

Now, I didn’t know these women’s relationship. Maybe they didn’t even want to be seen next to one another, let alone photographed together. You just don’t know in that moment, so you proceed with caution.*

I ask Mrs. King, and she graciously agrees to do a photo with Lena and Mrs. Onassis.

Then, because I’d learned early on that people at this level don’t like surprises—you have to tell them upfront—I go back to Mrs. Onassis and ask if it would be okay if Mrs. King joins us for the picture. And she gives her consent.

I alerted the media. It was the largest number of photographers I ever had cover an event. Backstage there were so many flashbulbs simultaneously going off that for two solid minutes there was continuous white light. Here were Jaqueline Kennedy Onassis and Coretta Scott King, arguably the two most famous widows of the twentieth century, there on the same night, as it happened, and I had asked each for their permission to pose for a photograph that turned out to capture a moment in history.

***

*Note: At the time, Joshua Ellis did not know that Mrs. King and Mrs. Onassis had been photographed together 13 years earlier, at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral, when the then-Mrs. Kennedy came to pay her respects. But the photos from this 1981 meeting would be the last taken of these legendary women together.

Joshua Ellis is at work on a book about putting the fun into the art of publicity. For more information about him, his one-man show, Call My Publicist: The Starry Education of a Broadway Press Agent, or his work as an ordained Interspiritual minister, visit www.callmypublicist.com.

Portions of this interview are featured in Paul Quinn’s forthcoming book, The Big Ask.

Cover image/ banner photo licensed by iStock Royalty-Free Images

What a great story and interesting life this man has lived. Thanks for this walk down memory lane.

Wonderful interview and fascinating stories

This is wonderful and priceless material to read. I am very proud to be a good friend of many years to Josh and know him to be a true professional and a credit to his life’s work.