Could a single question get a bomber to confess? Could “playing dumb” catch an arsonist? What happens when you ask for the truth from powerful people who don’t want to answer truthfully?

Cynthia Beebe is a retired Senior Special Agent with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) under the Department of Justice. She spent 27 years investigating bombings, arson, murder, illegal firearms, gangs and other crimes and was the first woman to earn the coveted “Top Gun” award at the ATF Academy, where she later worked as an instructor.

Beebe is a member of the International Association of Bomb Technicians and Investigators (IABTI), the International Association of Arson Investigators (IAAI), and Women in Federal Law Enforcement (WIFLE). She has a BA in English Literature and a Masters in Journalism, both from Northwestern University. Her book Boots in the Ashes: Busting Bombers, Arsonists and Outlaws as a Trailblazing ATF Agent, was published in 2020 by Hachette Publishing.

Paul Quinn: Cynthia, I often ask people about “the ask that changed everything” for them. Having read your book, I believe that in one of your bombing investigations it was a single question about a red toolbox?

Cynthia Beebe: Yes, the Lenius case.

[In 1993, in Niles, Illinois, a pipe bomb planted in a red toolbox exploded, killing a young father and his dog and gravely injuring his wife. The bomber, William Lenius, is serving a life sentence.]

Paul Quinn: At the very start of the investigation, you and a local detective brought Lenius in for questioning.

Cynthia Beebe: And the sergeant I was working with was a very good detective. But he was doing most of the talking and I was listening, and at one point I saw Lenius leaning forward and thought he was going to confess. But the detective didn’t notice and kept talking. And I thought, We’re gonna blow this if this detective doesn’t give Lenius a chance to gather his thoughts and speak.

But I didn’t want to sit there elbowing the sergeant, because Lenius was a smart guy and would’ve noticed that. So, I finally asked Lenius if he wanted to speak to me alone. Lenius said yes, and the sergeant stepped out.

Paul Quinn: Which turned out to be a very intuitive and timely ask.

Cynthia Beebe: And I have to give the sergeant a lot of credit because that could not have been easy for him to take that from me, a woman, a decade younger than him. He was in his own department and had to go out in the hall with his chief standing right outside the door and say, Chief, she asked me to leave. There were plenty of guys I worked with who would’ve refused to do that.

Paul Quinn: And when you had Lenius alone, the two of you were silent for a long time before you asked him a single question. What was that question?

Cynthia Beebe: I asked him, “Where did you get the red toolbox?”

He answered, “It was in my garage.”

At that moment, I knew I had him. And then he was willing to spill it all out, thankfully.

Paul Quinn: What do you see as the relationship between listening and building trust?

Cynthia Beebe: That’s a great question, and a very tricky one. So, there were over 100 of us in the room being trained in Reid interviewing [The Reid Technique of Interviewing and Interrogation for Criminal Investigators]. The trainer – who may have been John Reid himself, I don’t remember – said, “Ok, everyone, who makes a better interviewer – men or women?” And I was sitting near the front row and said, “Women!”

And he said, “You’re absolutely right, because women listen.”

I’m not saying that men can’t or won’t listen, but routinely a woman is more willing to listen, especially to a man. And I found that very helpful in getting guys to confess or give me admissions, which are facts you can use in court.

The biggest failure in most professional interviews is the interviewer cuts the subject off. I always wanted people I interviewed to think I respected them and therefore they would trust me. If I had cut them off two minutes too soon, I wouldn’t have gotten their trust or the information I needed.

Paul Quinn: I imagine it was challenging in many cases, as a federal agent, to try to appear neutral and non-threatening as you attempted to gain people’s trust?

Cynthia Beebe: I was always acutely aware when I was interviewing someone that I was an ATF agent, and that as an agent I had a lot of power. We’re an enormously powerful agency. There’s a big difference when you’re interviewing someone who’s a possible suspect, a victim, or a witness. My demeanor might be different depending on who I was interviewing.

But the one thing I never wanted any of these people to think — not even a brutally evil man like William Lenius — was that I was looking down on them. I always wanted them to feel I was being respectful toward them. And I always was.

Paul Quinn: Listening sounds like it was an important part of showing respect and earning trust. Were you ever surprised by the trust suspects gave you?

Cynthia Beebe: Yes. At the end of every interview I’d always ask, “If I think of another question, can I come back and interview you again?” And people always said yes, including people for whom it was not in their best interest to say yes.

So, bad guys really shouldn’t talk to me. They should say, “I’m sorry, I want to talk to my attorney.” That is the right thing to say if you’re a bad guy. With forensic science as extraordinary as it is today — far more advanced than when I became an agent — and the amount of CCTV out there and public information on Google, your best bet, if you’re a bad guy, is to not talk.

Paul Quinn: Noted! What’s the key to interviewing a witness effectively?

Cynthia Beebe: Quite often, the longer you keep an interview subject talking, they’ll remember more — “You know, come to think of it I think he had a limp” or “I don’t think he was wearing a coat.”

But not every agent has that skill set. Some are well suited to be interviewers and some just don’t have the interest. If you have an investigator who doesn’t want to work on an arson case, for example — because arson cases are usually really complicated investigations and take a ton of work — it’s idiotic to assign that investigator to an arson case.

So, it’s really important that the investigator conducting the interview is interested in solving the crime. The interviewer has to go in wanting it to be a successful interview.

Paul Quinn: As a Columbo fan, I have to know: What’s the value of playing dumb in investigations?

Cynthia Beebe: I can’t tell you how many times I’ve played dumb with bad guys. You’re interviewing them and they haven’t yet confessed or whatever, but maybe they’re telling you how they would’ve committed the crime or built the bomb and you’re like, Oh, sorry — could you explain that to me again? With the Ashby arson case I knew he did it right away.

[In 1991, Arthur “Daniel” Ashby torched his hobby shop and warehouse for the insurance money and told officials it was an electrical fire. Three firefighters were injured in the blaze. Ashby served six years in prison.]

I talked to Ashby for six or eight hours. He knew he had to talk to me because if you file a claim for insurance for a fire, you must by law talk to investigators or the insurance company doesn’t have to pay. So, he knew he had to cooperate. I never wanted him to know for one second that I was certain he had done it, and he never did.

Paul Quinn: You wrote this in your book about that conversation with him: “I did my best to appear ignorant of switches and electronics, blaming my repetitive questions on my failure to understand what he was telling me.”

Cynthia Beebe: Yes, and I did that kind of thing over and over in my career. Virtually every suspect I interviewed was a man. Women don’t tend to use guns and make bombs and commit arson. I needed to get them to confide in me, by playing far more confused than I really was and pretending to have no insight into people’s motives.

Paul Quinn: Which, unfortunately for these men, lowered their guard by playing right into their negative beliefs about women’s intelligence?

Cynthia Beebe: Exactly. That also worked for me in the Kagan case.

[Richard Kagan was a Chicago lawyer who paid members of a motorcycle gang to plant a bomb in his wife’s car. She safely escaped the explosion and Kagan tried to convince police that he, not she, had been the intended target. He was sentenced to 42 years in prison.]

When I first interviewed Richard Kagan at his office in downtown Chicago, I wanted him to believe that he could bamboozle me, because then he would talk more. It was the only thing that would work with a guy like him.

He knew he had to talk to me, because if any law enforcement officer had walked in there and Kagan had said, “I want a lawyer, I’m not talking to you,” it would’ve triggered our radar. He didn’t want to do that, so he had to appear to be cooperative. When I first talked to him It was great fun – because I knew he did it and was well on my way to proving he did it. So that was a blast. I just loved doing that.

When I left him that day, I wanted him to be uncertain of who I was and uncertain as to whether I thought he had tried to kill his wife. But I didn’t want him to think he’d gotten away with it, either, because, for the sake of his wife, Margaret, I didn’t want him to think ok now I can go and kill my wife because this agent’s so dumb they’ll never catch me.

So, I didn’t always play the dumb blond. Sometimes it paid to let suspects know I was as smart or smarter than they were. But if you say, “I know you did it,” you need to already have all the proof.

Paul Quinn: Of the Kagan interviews, you wrote, “They were simple questions and I knew the answers, but I wanted him to say a lot as I wrote in my leather notebook.” Tell us more about that notebook!

Cynthia Beebe: At that time, we didn’t often record interviews electronically. But, thankfully, one of the reasons I was as successful as I was as an agent was that I took copious notes during the interviews. Plus, it’s a way to kind of relax the person you’re interviewing because you’re not staring at them the whole time.

Particularly when they were saying stuff that was vital, I’d emphasize it in my notes so that when I was on the witness stand, I could testify that I asked the suspect once and went back and asked again and he said the same thing or something similar.

Paul Quinn: Final question, Cynthia: did you ever ask an unpopular or risky question?

Cynthia Beebe: Yes. There was a Special Agent in Charge (SAC) named Joe who I liked and who’d been very good to me. I was working major cases, so I really knew him. He was a good guy who cared about his agents. But some people at the top wanted to force him out of Chicago, so they started rumors about him that were demonstrably untrue and transferred him out of Chicago, which was basically a demotion. It was humiliating for Joe.

Not long after that, there was an ATF conference in downtown Chicago. Probably 170 people in the room including the agency director who came in from Washington. I was sitting in the middle of the audience. Toward the end, the director asked if anyone had questions. My intention wasn’t to embarrass the director or put him on the spot, but I said,

“Joe was very popular, and I thought he was a great SAC. Could you explain to us why he was moved?”

I could tell by the director’s face and the faces of the whole panel up there — you could just sense it in the room — that I had overstepped my bounds.

I was just a street agent, not a supervisor, not in management. But I was very high-profile and successful. I knew that because we were in public, the director couldn’t start swearing at me. So, he had to stand up there and do a song and dance about how removing Joe was the hardest decision he’d ever made and blah blah blah.

I had asked for Joe’s sake because he wasn’t there. And I guarantee you Joe heard about it.

Later I heard from senior agents that my question had pissed the director off. Apparently, he wasn’t happy. Later, agents said to me, “I can’t believe you asked that!” But I didn’t ask it disrespectfully and he didn’t answer it disrespectfully.

Paul Quinn: Any advice to people who might be tempted to ask their employers similarly loaded questions?

Cynthia Beebe: Be sure of your standing in the organization; I was a productive agent. Don’t ask in a disrespectful manner. Don’t put yourself in a bad position – unless it’s worth it. And be willing to pay the price.

Cynthia Beebe is currently in negotiations to host a podcast about her law enforcement career — follow this post for an update.

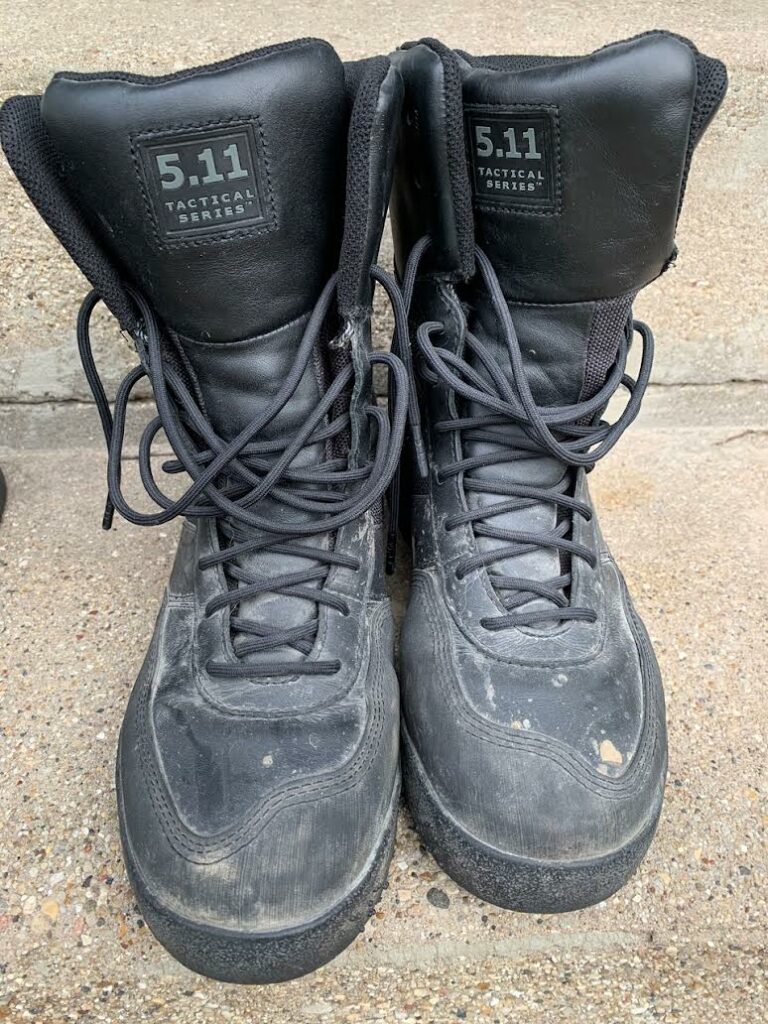

Photos courtesy of Cynthia Beebe. Fire photo public domain.

Excerpts from this interview are featured in Paul Quinn’s nearly completed book about the importance of asking, The Big Ask.

I want to read this book! What an interesting job and woman. Thanks