To Keiran Meeke’s way of thinking, tourists and travelers are not the same. Tourists are spectators. But travelers, he says, engage and learn from people. And that can be transformative. It can even give you better photos, a private viewing of the Georgian National Ballet, and a thrilling gallop on the Pony Express.

Born in Northern Ireland, journalist Kieran Meeke began his writing career with London’s award-winning Camden New Journal and then as a restaurant critic for the Daily Mirror. For ten years he was features editor of Metro, the United Kingdom’s highest-circulation print newspaper. His interest in the offbeat, hidden, and obscure inspired him to develop Secret London, a website he maintained for 15 years.

Kieran Meeke was also editor-in-chief of TRVL, a travel magazine voted best iPad magazine in 2012 and the highest rated on iTunes, with 1.5 million readers. The publishing software was eventually bought by Apple to form the basis of Apple News. He has explored more than 100 countries, lived in eight, and has landed (for now) in Kerry, Ireland. Kieran’s travels are beautifully captured in words and pictures in his blog, Inherit the Earth.

Paul Quinn: Kieran, the photos from your world travels are absolutely stunning. You first came to my attention many years ago when I read a piece you wrote about asking people permission to take their photos rather than “stealing” candid shots. Would you tell us about that?

Kieran Meeke: At TRVL, I was lucky enough to spend time on assignment around the world with many great travel photographers, and every one had a different approach. One or two liked taking candid shots which, after a while, I began to consider disrespectful. I much preferred working with those who took the time to ask people for permission, and I feel they got much better photos.

Paul Quinn: Don’t you lose spontaneity that way?

Kieran Meeke: That’s the criticism. But most people are already very aware if someone has a camera in the vicinity, and there’s a lot of posing in daily life anyway. There are very few of us who are not completely self-conscious. It’s a much warmer interaction when you talk to people and sort of become instant friends. They start volunteering things like, “Oh there’s something over there you should see and people over here you should talk to.” It’s just a much better experience.

Paul Quinn: Better than hiding behind the camera?

Kieran Meeke: Yes, because if you’re walking through a town or city or countryside sneaking shots of people you’re not interacting, you’re being a tourist, not a traveler. You’re not learning very much.

So, asking for photos completely transforms that experience, to start seeing people as people not as objects. That’s particularly important today when we are obsessed with looking at life through our phone screens.

Paul Quinn: How did you feel when you stopped taking photos secretly and asked your subjects directly?

Kieran Meeke: I felt much healthier mentally and more engaged, even when people said no. People don’t ask because they’re scared of the no. I used to be concerned that if I asked for their photo, they’d get annoyed or even angry with me and it would create a scene of foreigners shouting at me.

So, it’s like a lot of things in life, you build up the fears in your head. You know, the Mark Twain quote: “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.” Learning to ask is about confronting your own fears.

Paul Quinn: Journalists lead with their curiosity, and I would think it’s even more vital that travel writers be curious, or what’s the point of travel? Have you always had this curiosity or is it something you’ve developed over time?

Kieran Meeke: It’s got stronger and stronger. Like a lot of writers, I consider myself very shy. I spent almost a year in hospital when I was 11/12. I was the only child in a military hospital, and confined to bed, so I became very introverted.

All through my teens my head was buried in books. I was not very good at relationships and talking to people, but I became a very good listener and observer. It was when I got into journalism that I had permission to express my curiosity about people and ask them questions.

Paul Quinn: I feel similarly about writing my book. It gives me permission to talk with interesting people about very interesting topics. It beats small talk!

Kieran Meeke: Right. I don’t do chit-chat. I’m very bad at “It’s a lovely day—did you see the game last night?”

Paul Quinn: You had a website called Secret London. How did that come about?

Kieran Meeke: I was based in London for a long time but not really liking it. And I realized that I just didn’t know it as well as places other places I’d lived that seemed more exotic, such as Hong Kong, Paris or Johannesburg. So, I had the idea to come at it as if it was a foreign city and just start walking around. That’s what I do in a new destination; I walk around and just get a feel for it. It’s a lot easier for a man, of course, to walk around on your own, particularly in the evenings.

So, I started discovering things that ended up as a collection of some of the quirkier things about London, often hidden in plain sight like WWI Zeppelin bomb damage on a wall, or the old street under Soho. The more I did it the more fascinated I became, and the more I fell in love with London. If you wander around places and start asking questions about the shop or the street or the house people are usually pretty thrilled to open up to you.

Paul Quinn: Have you ever asked permission for something and been really surprised to get a yes?

Kieran Meeke: I was in Georgia, in Tbilisi, and saw this interesting looking door. I pushed it open and walked into a room where the Georgian National Ballet was rehearsing. I had a camera with me and asked if I could take some photos and they said, “Oh, sure.” I must’ve spent an hour with them. It was a whole private amazing show, the athletic dancing with the swords and the leaps and kicks.

Paul Quinn: Sounds like you had terrific luck and timing.

Kieran Meeke: Georgia may be the most hospitable country in the world. But I think if I’d called and said I wanted to photograph the National Ballet in rehearsal it would’ve become bogged down in emails and PR. This was a pure accident. So, asking spontaneously was probably much more powerful than asking in advance.

Paul Quinn: I also love the fact that you saw an interesting door and thought, why not open it? That’s such a perfect analogy for asking. As a global traveler, are there questions you can ask in some cultures but not in others without being rude?

Kieran Meeke: That’s such a big question all over the world. You need to know the culture. For example, during ten years living in Southern Africa, I learned that it’s incredibly rude to ask a poor Black farmer how many cattle he has. It’s like asking how much they have in the bank. Now, if I asked you that question, Paul, you could say “Mind your own business,” because we’re social equals.

But if I as a white foreigner ask that African, he might feel obligated to answer – for all kinds of complex cultural and historical reasons. He’s going to be fairly annoyed yet not able to show it because losing your temper (or rather showing it) is also a big cultural no-no. You’re abusing a major power imbalance.

Paul Quinn: How do you try to adjust that power imbalance?

Kieran Meeke: I might ask if there’s anything they want to ask me, and that can be a good way into deeper conversations. You just have to be really aware of the privilege you have there—like many other places—if you’re a white foreigner, the baggage you carry.

Some parts of Africa are still affected by the memory of colonialism, for example, particularly South Africa with its history of Apartheid. Hospitality is such a strong cultural feature in so many places but that power imbalance still exists and can still distort any interaction.

Paul Quinn: Can you give us an example of that?

Kieran Meeke: I’m thinking of the township tours in and around Cape Town and Johannesburg. I’m very uncomfortable with most of them. They can be a sort of “poverty porn” for westerners going to see poor people’s homes.

I’ve seen people abuse that power imbalance by saying, “Oh, can I have a look in your cupboard?” You have to be really aware of when it’s right to ask and when it’s not; of when you should just observe, listen and learn. In other words, don’t even ask, if people might feel they have to say “yes”.

Paul Quinn: Were there any asks that changed your life, personally or professionally?

Kieran Meeke: A couple of them. I was going into the Metro office one day and there was a brand new, yellow Harley Davidson 850 Sportster parked right outside. I asked in the office, “Whose Harley is that?” and found out it didn’t belong to anyone; it had just been delivered for a test ride. But there was actually nobody on the features desk who had a motorbike license. So, I went and passed my license and so became the motoring correspondent (laughs).

A gorgeous $20,000 Harley V-Rod was the first motorbike I was asked to review after I got my license. I remember riding it across Tower Bridge and tourists were photographing me! So, asking, “Whose motorbike is that?” began a very interesting part of my career. I eventually passed my race-driving license and drove everything from a tank, through a tuk-tuk, to an F1 car on the race track.

Paul Quinn: You clearly know how to seizes opportunities! What was another important ask in your life?

Kieran Meeke: I’m obsessed with horses. I had a friend in Africa, Micky, a London-Irish bookmaker who kept some thoroughbreds for the racetrack. He was a former professional jockey, and his son is Sean Levey, the first Black jockey in Britain. I asked Micky if he would teach me to ride and he agreed. I was 35. I’d never ridden before.

Micky put me in the ring on one of his horses and eventually I was riding out with him to train and exercise the horses, three a day at weekends. We often rode in a game reserve, among herds of wild animals. So, I became a very experienced rider. I was so, so lucky. It was the right ask, right time. Because of that, I’ve been able to work as a stockman [cowboy] in Australia, ride with the Bedouin in Jordan, and enjoy week-long pack trips in the Canadian Rockies.

Paul Quinn: A horse figures prominently in a story you wrote in 2011 for National Geographic Traveller about your travels in Syria. I just read it this morning. I love your writing, but I found this passage particularly beautiful:

“Mythology also seemed to be coming to life as the sun fell again and, amid the ruins, I spied a beautiful black stallion pawing the stones, its rider sitting awhile to admire the view. Then he spurred his mount into a gallop home, a glorious streak of darkness in the falling light.”

Kieran Meeke: That was in Aleppo, just before the civil war. It’s one of my big regrets, that I didn’t ask if I could ride that horse. I was just dumbstruck by how beautiful the scene was. It was an absolutely magical moment. I felt like I was in a dream. Otherworldly. By the time it even occurred to me to ask, they had galloped off into the night. But, oh, I still feel it as such a missed opportunity and I wonder what happened to both horse and rider during the war. To paraphrase the old saying: you only regret the things you don’t ask.

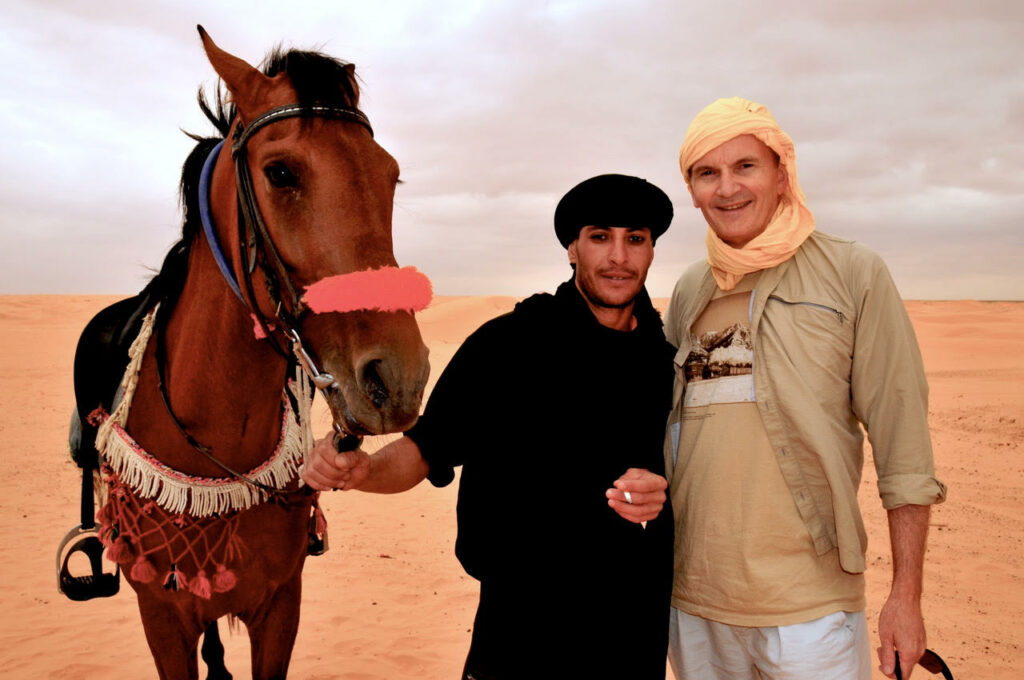

A few years later I was in the Tunisia desert, on a camel ride, and the guide was on a beautiful Arabian horse. When I asked to ride it, he was quite surprised because the point was to ride the camels. But he agreed to let me sit on it for a photo and when he saw I knew what I was doing, was then happy to let me take it for a canter across the dunes. I felt in some way I’d compensated a little for Aleppo.

Paul Quinn: Have you ridden horses in the U.S.?

Kieran Meeke: I rode the Pony Express across America. Every year in June they do a re-ride of the original route from St Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. It’s about 2,000 miles and I rode two stages, one out of Casper Wyoming and one across the plains to Independence Rock. It’s supposedly called that because if your wagon wasn’t there by July 4, you wouldn’t reach the Rockies by winter.

I was lucky to be invited to do that and as far as I know was the first non-American to do it since the original pioneers, many of whom of course were English or other new immigrants. The Pony Express ran for just 18 months, until the cross-continental telegraph was finished, and its founders went bankrupt.

Paul Quinn: Kieran, as a journalist, you’ve interviewed a lot of big names — Tony Curtis, Tracy Chapman, Robert Duvall, Gladys Knight, James Cameron … What are a few of your best interview tips?

Kieran Meeke: One of the most powerful questions to ask at the end of an interview is, “Is there anything else you want to talk about?” Sometimes the whole interview ends up being built around that question because it prompts a conversation that’s much more spontaneous than the formal interview. And, of course, one of the tricks of the trade is to leave any really controversial questions to the end, so if the person walks out or slams the phone down you’ve already got something in the bag.

Paul Quinn: Any memorable surprises from those interviews?

Kieran Meeke: I remember being absolutely amazed interviewing Yo Yo Ma because he had done his research and asked me questions. I just basked in it: Wow — Yo Yo Ma is asking me questions! It may have been a killer PR move but I think it actually was genuine. Either way it was brilliant and lovely.

Paul Quinn: What’s next for you?

Kieran Meeke: I’m doing a lot of hiking, in Ireland and Spain mostly. So I’m working on a website and a video project aimed at that. I qualified as a hiking leader just before these last two years of lockdown, during which walking boomed, of course, so my timing was fortuitous.

Paul Quinn: Well, my last question will come as no surprise: Is there anything else you want to talk about?

Kieran Meeke: There isn’t! I’m a writer, not a talker. But thanks—I’ve enjoyed it.

Paul Quinn is author of a nearly completed book about asking as a life skill, which features portions of this content.

0 Comments